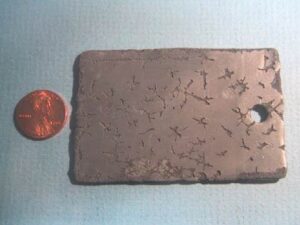

Ultrasonic cleaning is widely used for removing particles from surfaces. It is generally agreed that the high energy of implosions of cavitation bubbles break the bonds holding particles to the surface being cleaned and that liquid motion (streaming) carries the particles away once they have been dislodged. However, it is also well known that ultrasonic cavitation and implosion will generate particles as material is eroded from surfaces as cavitation bubbles implode in proximity to them by a process of ultrasonic erosion similar to that seen on a ship’s propeller. A glass beaker, aluminum foil or a lead coupon subjected to long term exposure to ultrasonic cavitation in liquid provides adequate evidence that ultrasonic erosion is real.

This leads to an interesting question – – How do you achieve a balance between the removal of foreign particles and the generation of particles from the substrate to give a completely particle free surface? Or, asked in another way, when does cleaning stop and the replenishment of particles due to surface erosion begin.

Published articles widely support the notion that virtually all substrates generate particles due to ultrasonic erosion and that although the rate of particle generation may diminish or “level off” over extended exposure times there is no termination point. Surfaces continue to shed particles indefinitely. This leads to the question of how is it possible, then, to provide a surface with absolutely NO particles. The simple answer, it would seem, is that it is not. But let’s consider what means might be used to leave the smallest number of free particles.

One way might be to reduce ultrasonic intensity as cleaning progresses. Again, published articles support the notion that the rate of particle generation is directly related to ultrasonic intensity. Logic would say that particles eroded from a surface might be displaced from the surface by slightly less ultrasonic energy that was required to produce them in the first place. In the end, when the ultrasonic intensity reached zero, the minimum number of particles released by erosion would be left behind.

However, published articles also verify that rate of surface erosion is reduced and that the size of particles liberated by cavitation erosion becomes smaller at higher ultrasonic frequencies.

Combining the ultrasonic intensity effect and the frequency effect would suggest that the most effective way to produce a surface free of both foreign and particles eroded from the surface would be to cycle through a series of ultrasonic bursts with increasing frequency a number of times with reduced power at each iteration thereby successively removing smaller and smaller particles while producing fewer and fewer particles as a result of cavitation erosion.

Although ultrasonic hardware is readily available that has the ability to vary both frequency and power, it seems that most researchers have investigated only the effect of frequency on the ability to remove particles and produce a surface free of particles. This approach, of course, does not take into account the generation of particles from the surface as mentioned above. It also excludes the effect of successive use of multiple frequencies as I discussed in an earlier blog which may provide a significant benefit.

– FJF –

Water – De-ionized – Hints

Water – De-ionized – Hints  A Fond Farewell to John Fuchs

A Fond Farewell to John Fuchs  Millipore Testing – Evaluation by Particle Counting

Millipore Testing – Evaluation by Particle Counting  Tape Test for Cleaning Revisited

Tape Test for Cleaning Revisited